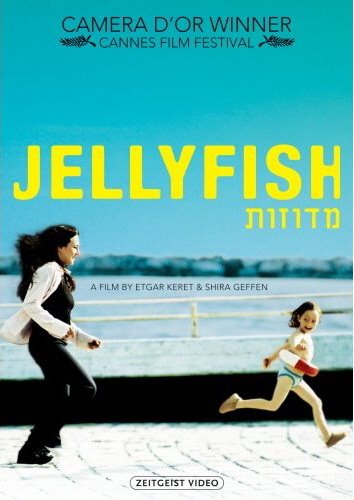

Shira Geffen’s Meduzot, Jellyfish, 2007, was a great success inside and outside Israel. The movie, which is set in Tel Aviv, tells the story of three women. The three stories appear to have three plots that are unconnected. Though the movie can be approached from different angles, I here chose to examine it from a feminist, or gendered, perspective.

Mary Gentile explains that the definition of a movie as a feminist movie depends on the viewer rather than on the movie itself.i Jellyfish is a typical movie to question gender roles in Israeli cinema, as will be explained below. Following a short outline of the plot of the movie and the director’s background, this article will focus on feminism and writing gender in cinema in general and in specific in Israeli cinema; the meanings of gender and gendered perspective of this film in the Israeli context; the movie’s style and motif in the context of women’s films; the role of women in the film and the role of the “girl”. It will touch briefly on issues of race, neglect of the Israeli – Palestinian, sexuality and “Finding a Voice”.

The Movie

The film opens with leaving Batya’s boyfriend leaving her, a young girl who works at a wedding catering service. That evening Batya finds a girl on the beach of Tel Aviv who walked out of the sea. The five-year-old girl does not speak. As Batya decides to take care of the girl, Batya begins to unravel a connection between the child and a repressed and unresolved childhood trauma of her own.ii In her search for the parents of the girl, Batya’s relation with her family crumbles, while the relationship between her and a female photographer develops.

The second plot revolves around a newly-wed couple. Due to an accident at the wedding, the bride breaks her leg. Rather than spending their honeymoon in the Caribbean, Keren and Michael turn to a small hotel on the promenade of Tel Aviv. Perhaps the broken leg indicates the first fractures in their relationship, which come at a peak when Michael meets a poet in the hotel. While this new ‘femme fatale’ intimidates Keren, the new bride’s indifference toward life connects her to Batya’s indifference. This indifference opens the movie when Batya refuses to act upon her break-up. Similarly, Keren demonstrates a lack of action to leave her hotel room. The difference, however, is that Batya choses to retreat in silence, whereas Keren complains.

The last story line involves Joy, a Filipina caretaker of a stubborn and tough elderly woman, Malka. Malkahas a difficult and complicated relationship with her daughter, Gila, an actress from Tel-Aviv.

The movie touches upon the relationship between children and their parents. This is demonstrated not only in Malka’s relationship with Gila, but also in the relationship between Batya and her parents, Joy and her son, the photographer and her parents, and the elderly woman Joy takes care of at first and her children. Although the three storylines seem to be related, there is no connection between any of these women with the exception of Joy walking into Batya on the street. Nevertheless, all are connected to the sea.

Shira Geffen, born in 1971, is mostly famous in Israel as a poet and playwright. Together with her husband, Etgar Keret, she directed and produced the movie. Highly pregnant at the time of shooting, Geffen claimed that film productions are more a matter for men.iii Nevertheless, the movie is centered on the concept of women roles in Israel.

Feminism and the Gendered Perspective in Israeli Cinema

Orly Lubin explains that the feminist text does not simply deal with the female experience but it is a text that allows the female reader to place her subjectivity while reading.iv Others have argued that an important element in feminist cinema is “perspective”v, such as whether the movie is set within terms of men or women.

Yael Munk explains that throughout the years, women were mostly portrayed in roles created as the object of male fantasies. Women were untouchable; the camera positions would have a frontal focus, outlining the boundaries of the “desired object.” Women’s bodies, and womanhood as a whole, were subjected to a process of objectification. The male gaze was dominant in general cinema worldwide and distorted the representations of women. In response, women sought a voice of their own by creating movies themselves.vi

Cinema then is an appropriate tool for women to have their voices heard.vii Miri Talmon claims, in this context, that cinema does not present us with our identities as they exist, but allows us to negotiate them, to discover who we have become, and to pose ourselves as new kinds of subjects, and rediscover the hidden history.viii Gilad Padva adds that Israeli cinema also experiments with the young sexual communities for a wider audience both inside and outside of Israel.ix

Dorit Naaman, however, accuses Geffen of neglecting the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in Jellyfish.x The overall focus on sex and gender makes it impossible to not deal with this movie from a gendered perspective. Although some of the protagonists’ concerns are universal and relate to any person, regardless of sex or gender, such as marriage, children, work, and migration, the movie approaches these topics from a gendered perspective. The perspective is a feminine one in this case, since here these issues only viewed within the movie from the perspective of a woman. The men that feature in the movie are nothing but a tool for plot. The fact that the film starts when Batya’s partner abandons her, highlights the focus on Batya and other women.

However, the question follows whether we should consider Jellyfish to be a feminist movie or a gendered movie. One could understand feminism as a political movement, whereas gendered writing would be a stylistic choice. Similarly, Yaron Peleg categorizes the Judith Katzir’sxi oeuvre as feminist. His choice is based on the lack in Israeli literature of works that deal with femininity, without being embedded in the Zionist metanarrative.xii Hence, it is possible to interpret Jellyfish as a feminist production. Monk adds that, in general, women’s films in Israeli cinema focuses on or at least indicates Israel’s state of war.xiii Ella Shohat observes that there is no place for feminism in the Zionist discourse.xiv Peleg explains that all prose is always connected to the Zionist metanarrative in one way or another, such as either as serving the Zionist discourse or opposing it.xv

Style and Motif

Style and interpretation are important to cinema globally. Monk claims that while Hollywood films are increasingly turning to narratives that are realistic enough to make the spectator feel that what he sees is a mirrored possible reality, women’s movies do the exact opposite, that is to say, they break the cinematic illusion.xvi

Therefore, the surreal and symbolic style in Jellyfish is a choice. One may argue that Geffen and Keret are firstly authors rather than producers and they are famous for their surreal writing styles and short videos.xvii But it is clear that the film employs the surreal element to allow for an additional layer in which the status of women can be discussed; the theme of water.

Water can be interpreted as a symbol of transition, loss, or rebirth. Moreover, water neutralizes and is unspecified. Water has been the symbol of the woman throughout the ages.xviii The motif of water appears throughout the movie in different forms; Batya’s meeting with the child is probably the most blatant expression of this theme. Despite the leakage in her apartment, the landlord refuses to fix it. On the contrary, he raises the rent. When Batya brings the child home and leaves her alone for a moment, she is shocked to watch the child drink the drops as they splash down. Moreover, Keren constantly has a desire to see the sea, which leads to a room-swap with the beautiful poet. Joy, on the other hand, is desperate to buy a toy boat her son for his birthday.xix

Joy’s ship, that finds its way to her son, stirs an image of the ship that is described in Keren’s poem, and later in the poet’s suicide letter. The poem mentions that the ship is trapped in a bottle, as if in jail. Perhaps this symbolizes Israeli woman and the women in that society. After all, all the main characters are, one way or another, “restrained.” Joy is the only one to break out of her “bottle”. Maybe she has the freedom to leave her job? Maybe she completes her role as a woman, as she works to support and care for her child? The Jewish Agency, after all, has published that women who do not adapt to the Israeli the model and are considered often as if they failed their natural role as a woman and as an Israeli national. Unmarried women tend to feel greatest pressure to marry, and it is difficult for them to break away from the traditional Jewish role.xx

Meanwhile, even the jellyfish that are described in the poem mentioned above, are described as if they are people who are forced to cling to the ship and are forced into their confinement. Though the poem projects the jellyfish as people, the movie itself connects the metaphor of the jellyfish to women when, supposedly, a jellyfish turns into a 5-year-old girl. Indeed, the little girl who comes out of the sea represents the issue of childhood in Israeli society and the relation between parents and children and vice versa. This issue shall be further explained below.

The role of Women, Motherhood and the Place of Children

As much as the movie deals with the gendered perspective, so does it deal with issues of motherhood. Israeli society focuses on and is built on women. The woman is an integral part of Israeli discourse. Yet, simultaneously, the Israeli woman is not an individualist or ‘woman’, but she is a strategic pawn. In Israeli films, Lubin claims, the dominant mechanism is the social positioning of women; the professional status of women, their place in the community, and their family roles.xxi

The Jewish Agency’s words would explain the poet’s death. After all, she is single, has no children, and thus she is useless to Israeli society. In her suicide note she describes her feelings of belittling. However, Keren also describes these feelings before, although she is married. This paradox would lead one to suspect that there is a friction between the desired role for women and the realization of this role. Hence, the spectator only comes to know the horrible mother and, in general, a failure of a woman. Malka is unable to connect to her daughter. At the same time, Gila prefers her work over her mother. All relationships between parents and children are distorted in this movie. Joy at first works for a women who dies in loneliness. Apparently, her children were not very close to her either. Yet, her son makes an effort to help his mother, whereas the spectator is unable as to even catch a glance of the daughter’s face. We only hear her voice while she makes excuses as to not visit her mother.

The defect between parents and children is most prominently displayed in Batya’s relation to her parents. When she finds the girl on the beach, Batya resorts to talking to her father, who is a doctor, after not speaking for years He asks her about a job that she quit some time ago, while she is introduced for the first time to his girlfriend, who suffers from Bulimia. The father’s decision to date a patient, demonstrates his choice not to spend more quality time with his daughter. The hospital scene is especially telling. After a car accident Batya lays in the hospital. When her father utters his regret of not having been a better father, his girlfriend again requires his attention and Batya is left alone.

Nevertheless, he does express some form of remorse and worry. Batya’s mother uses her daughter’s hospitalization as an opportunity for her new campaign, in which she promotes a safe living for every Israel citizen. When Batya tries to reach for her mother, the latter is too preoccupied with her campaign and leaves without paying attention to her hurt child. The irony is that her mother constantly contacts Batya over phone, but refuses to visit her in person. Moreover, the campaign that she is so obsessed with concerns offering a “roof and security” to every Israeli citizen. Batya, however, lives without security. The one time the spectator is able to see her mother protecting Batya is in a painful scene when Batya runs away from the hospital and is standing in the pouring rain in her hospital pajamas at a bus stop. Behind her appears her mother’s campaign poster, featuring her mother with her hands held up in a triangle, symbolizing the roof she wants for all Israelis. Ironically, due to Batya’s stance, it seems that the hands are folded over Batya, as if protecting her from the rain.

Monk argues that throughout history, stereotypically female traits, despite their positive nature, have forced women to take part in political and public discourse.xxii Perhaps the irony that is present in the relationship between Batya and her mother. The relationship symbolizes the impossibility of Israeli women to combine being both a mother and the ability to fulfill a public role. This issue is also demonstrated in the dismissal of men bosses towards their female employees, such asthe wedding caterer who fires Batya and the photographer.

The issue of family relations is further explored through the image of the young girl who came out of the sea. It is unclear whether the child actually exists or if she is Batya’s projection of her childhood memories. We understand logically that the girl cannot exist. Nevertheless, the police officer asks her questions and attempts to talk to her in order to find her parents. The photographer captures her image on the camera. However, the girl does not speak. Everything we know about her is through Batya. That means that the girl is to some extent a projection of Batya’s childhood.xxiii This is enhanced by the questions of the police officer, “Where is her father? And where’s Mom?”.

Batya tell us that the child is five-years-old, and slowly she starts to remember where she recognizes this girl from after losing the girl and saying goodbye forever. She only remembers how to connect to the girl after watching videos depicting normal childhoods with a friend, perhaps her girlfriend, that are not her memories. It becomes evident that Batya grew up in a family that during a divorce. The disconnection between her family is symbolized by the lack of being able “to find the ice cream man.” Once Batya is able to deal with her situation, she once again finds the girl and they separate again, she finds the ice cream man.

We can see in comparison to other Israeli movies, which ignore the relationship between children and parents, thatJellyfish demonstrates the problem of motherhood in Israel. There are problematic mothers; mothers who do not know how to behave and interact with their daughters, mothers who are disconnected from their children, distanced from them both physically and mentally:xxiv Batya’s mother connects to her via posters and phone calls, rather than face to face. The communication is one-directional and exhausted from its own benefit, without attempting to understand Batya. As for the actress, Joy, and her mother, they are unable to communicate directly or show love, support and empathy. All is mediated via through the foreign care-taker and letters. Joy herself is a mother who stays in touch with her son through phone calls that are disconnected in the middle of their conversations. “These relationships are resolved one way or another at the end of the story.” Nevertheless, the solutions are not completely satisfying. Batya does not get her lost childhood back, Joy is able to send her son the toy boat, but is unable to return to him in person and the actress and her daughter remain on cold terms.

Hence, it is unclear whether the film is a feminist film or a movie with a feminine gender perspective. Feminist films are often assumed to have a stronger political character, whereas gendered movies merely focus on women’s perspectives. The distinction is hard to make according to Peleg’s explanation as laid out above. It draws attention to the status of women and it does this through a focus on family relations in Israel. The child, the jellyfish, in the theme of water, as well as its surrealist style allow for the reconsideration of the meaning of normative family life in Israel and the place of women and children in them. The neglect of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict causes to divert the focus on Israel in terms of violence and war, as is apparent in so many movies, and to have a critical look towards the social composition of Israel and the role of women in it.

This paper was originally a term paper for a Hebrew Cinema Seminar at Harvard. In the original more Hebrew sources were used, which have been deleted here for simplicity and length. The above is a shortened and translated version of the Hebrew original paper.

Bibliography

(all Hebrew translations are by the author)

Mary C. Gentile. 1985. Film Feminisms: Theory and Practice. Contributions in Women’s Studies, Number 56. Greenwood Press, London.

Dorit Naaman. 2011. “Rave against the Occupation? Speaking for the Self and Excluding the Other in Contemporary Israeli Political Cinema.” Israeli Cinema: Identities in Motion. Ed. Miri Talmon and Yaron Peleg. University of Texas Press, Austin. pp. 257-275.

Karen Hollinger. 2012. “Feminist Film Studies.” Routledge, New York.

E. Ann Kaplan. 1984 [1983]. “Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera.” Methuen, New York.

Yael Monk. Cinema and Gender. Tel Aviv University, department of Cinema and Television. Tel Aviv (Hebrew, translation by author). n.d.

Orly Lubin. 2005. “The Woman as Other in Israeli Cinema.” Israeli Women’s Studies: a reader. Ed. Ester Fuchs. Rutgers. pp. 301-316.

Gilad Padva. 2011. “Discursive Identities in the (R)evolution of the New Israeli Queer Cinema.” Israeli Cinema: Identities in Motion. Ed. Miri Talmon and Yaron Peleg. University of Texas Press, Austin. pp. 313-325.

Ella Shohat. 2005. “Making the Silence Speak in Israeli Cinema.” Israeli Women’s Studies: a reader. Ed. Esther Fuchs. Rutgers. pp. 291-300.

Miri Talmon. 2011. “The End of a World, the beginning of a New World: The New Discourse of Authenticity and New Versions of Collective Memory in Israeli Cinema.” Israeli Cinema: Identities in Motion. Ed. Miri Talmon and Yaron Peleg. University of Texas Press, Austin. pp. 340-355: p.340.

Websites

http://sophia.smith.edu/blog/fys186-01f11/2011/11/04/october-movie-review-meduzot/

http://www.e-mago.co.il/Editor/cinema-1798.htm

http://www.popmatters.com/review/jellyfish-meduszot

http://jafi.org/JewishAgency

http://filmmakermagazine.com/1310-etgar-keret-and-shira-geffen-jellysifh/