Construction, Deconstruction, Reconstruction

13 February – 29 March 2014

Ayyam Gallery,

143 New Bond Street

1st Floor

W1S 2TP, London

http://www.ayyamgallery.com/

Construction, Deconstruction, Reconstruction, Saudi Arabian artist Faisal Samra’s first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom, is a deeply personal journey through the creative and perceptive processes, which combines the principles of abstraction with clinical rational precision through photography, sculpture and visual media. The result is a powerful and challenging work which champions the human capacity for re-invention and presses the significance of individual re-assessment as the bedrock upon which transformation must occur.

In some ways, the exhibition is a direct outgrowth of Samra’s own struggles with the creative process. Since he began work as an artist in the 1980s, Samra has sought to push the boundaries of expression in the plastic arts, developing themes and forms until the work ‘rebels on itself and creates another pattern of expression’.

‘In the mid-1980s my major concern was to develop an artwork that eliminates the borders between different fields of the plastics arts,’ he explains. ‘In 1989, I dissolved the border between painting and sculpture by freeing the treated canvas from the frame, cutting it into organic shapes, and hanging it – either at an oblique angle to the wall, or in empty space. This treatment enabled me to open a dialogue between the artwork and its context. The canvas itself became the body of the work. In other words, the constructive materials became the form and the content of the artwork itself.’

C.D.R. is a direct continuation of this on-going creative process, which seeks to constantly recreate the form through innovative syntheses of mixed media form without compromising the aesthetic power of the art form. ‘I always want for my work to be joyful visually and provocative conceptually. When I produce art, it is vital that I enjoy the images that I have made, that I savour the visual factors that I have incorporated into my work.’ As a consequence, the conceptual core is never privileged over the aesthetic form. ‘I have to catch the viewer’s eye and then I can take him to other layers of meaning. I think that this also tells something about me, particularly about me as an artist.’

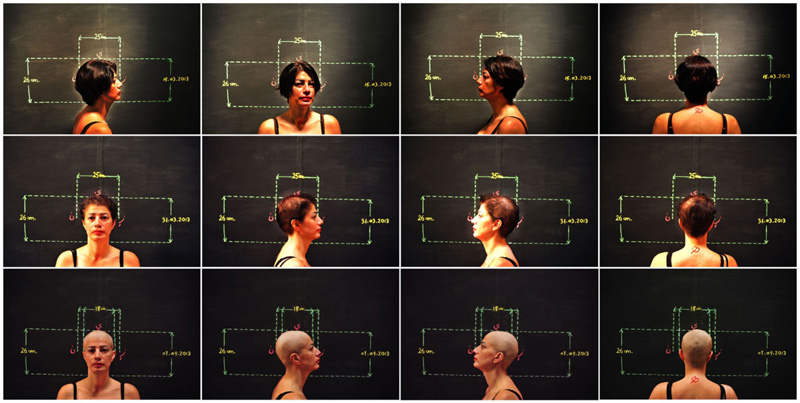

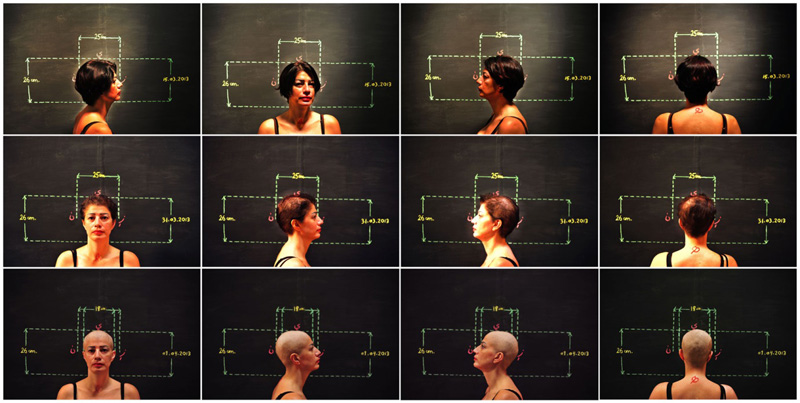

These themes – conceptual provocation, rational analysis and fluid reinvention – occur as constant leitmotifs throughout the C.D.R. exhibition. Upon entering the Ayyam Gallery, one is immediately struck by the division of the exhibition into black and white halves, and even more so by Zeina, which dominates the white half of the room. Zeina charts the journal of Samra’s wife before, during and after chemotherapy after a diagnosis of breast cancer through a series of triptychs, consisting of frontal- and side-profile portraits. Arising from their mutual desire to increase the awareness of others – ‘we learned much from that, therefore we wanted to share this experience with everyone, as it could happen to anyone’ – the measurements added to each image demonstrate Samra’s attempts seek rationality within an extremely emotional subject, and thus include the human body within the system of perpetual deconstruction and recreation that dominates his art.

Yet the C.D.R. cycle is not considered a negative by Samra, but rather an inevitability that must be accepted. ‘I think that CDR cycle is a fact of life,’ he adds, ‘which we cannot do anything to stop it, but we can use it.’ Accordingly, the process of personal re-perception and re-creation that Zeina’s recovery prompts is used as the platform from which the viewer is challenged to imbibe the C.D.R. process and retrace Samra’s own journey of discovery.

For Samra, this journey must begin with the self. In Liberating the Idol, Samra borrows from the Freudian notion of the ego to explore the notion of wholeness in one unit, versus the effects of fragmentation in the very same unit. Thus, Samra begins with a painstakingly-crafted clay idol, lovingly decorated with the word ‘Ana (‘I’) and gazing adoringly at its own reflection in a mirror, before recording himself unceremoniously smashing the idol on the ground outdoors. The work thus culminates in the idol, now decimated, hanging humiliated within a simple plastic bag. Only the mirror emerges unscathed.

Having dealt with the ego, Samra now turns to the senses. Blue Eye and Green Eye thus take visual perception through the C.D.R. method, deconstructing and abstracting the form of the eye with the same precise rational measurement that emerged in Zeina to establish a new way of seeing the world outside the self. Meanwhile, the use of vibrant primary colours upon the black background, both in the eye and its measurements, serves to stimulate the viewer’s own senses in engaging with Samra’s process, heightening the interaction between spectator and subject. This process is then expanded from the self to focus the individual on social and political change in The Chair, before finally, in Pencils, breaking traditional thoughts held since childhood and beginning the analytic process again.

It is in The Chair that the second intended recipient of the C.D.R. process is explored most fully – the wider social, economic and political structures that we, as individuals, inhabit. The Chair consists of a Louis XVI throne, symbolic of traditional power, inscribed with ‘Made in the Arab World’ and ‘Global Economic Power’, before being destroyed and replaced with ‘Made in the Occidental World’ and ‘Global Economic Power’. To achieve this, the destructive process played before our eyes, as the artist, anonymous in a mask, bluntly demolishes the chair with an axe; only the charred remains are physically retained.

Here, unfortunately, Samra sees the C.D.R. process in the Middle East as largely one of outside imposition. ‘The Middle East has been under a destruction and reconstruction ever since after the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement that divided the region when the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the Western Super Powers,’ he clarifies. A century later, with Iraq undergoing reconstruction after the destruction of the 2003 US-led invasion, the vulnerability of the region to the imposition of this process from outside remains as pertinent as ever. Yet, just as the negatives of the C.D.R. process are symbolised in The Chair, so too are the positives: thus the anonymous masked man, applying Samra’s abstraction through rationally precise methods, emerges as the force through which the Middle East’s own re-creative process must begin.

Construction, Destruction, Reconstruction as an exhibition is, in fact, itself a representation of its own artistic method; Samra discloses that ‘there are more works of C.D.R., only we selected what the gallery space can take’. Yet this lends itself well to the artist’s intention, as the confines of the gallery enable the spectator to experience his work as a totality. As a consequence, the panoramic quality of the exhibition renders us fully aware that this is not a finished project, but a fluid, never-ending development. ‘C.D.R. has not finished yet,’ concludes Samra, ‘it’s only the start of the “Cycle”.’

Follow Leon on Twitter @leonkuebler